DLHA Staffwriter

Representation of vibrio cholerae, the germ (bacteria) causing cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small bowel caused by some strains of the bacterium known as Vibrio cholerae.

Common sources of exposure to the bacterium range from ingestion of contaminated food including vegetables that is grown or rinsed in impure water; to ingestion of street food lying uncovered for hours. Due to poor or lack of effective sanitation and pipe-borne water supply especially in developing countries like in Africa, the commonest source of the contamination is human feces containing the bacteria. Under-cooked sea foods are also a common source of the infection.

.jpg)

Humans are the only animal affected by cholera.

It is a disease that is common in peri-urban slums with rapid population growth in which large numbers of people that moved from rural areas into big cities, live in conditions with poor basic facilities.

Cholera affects an estimated 1.3 –4 million people worldwide and causes 21,800–143,000 deaths a year1.

Cholera affects an estimated 1.3 –4 million people worldwide and causes 21,800–143,000 deaths a year1.

The majority of cholera sufferers live in developing countries of Africa, Southeast Asia and Haiti. The disease is rare in developed countries.

Children bear the highest risk of the disease as well as the highest death rate.

The risk of death among cholera patients can be as low as 5% and as high as 50% Lack of immediate access to treatment results in higher death rates.

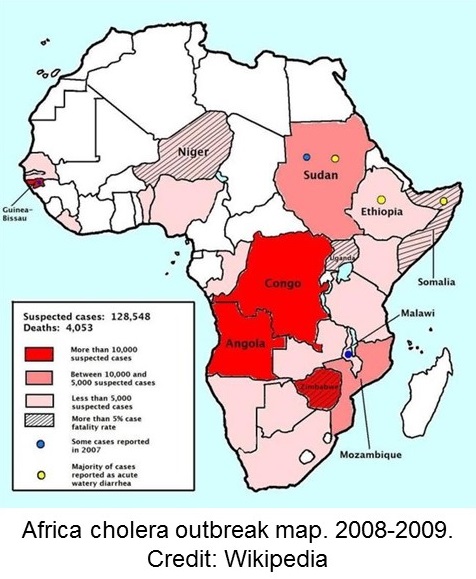

Cholera occurs as both sporadic outbreaks (as in the most recent outbreak in Nigeriia) as well as chronically in most countries of Africa (see image).

Example of African countries with reported sporadic outbreaks as well as chronic occurrence of cholera in some areas include, Nigeria, Liberia, Kenya, Tanzania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, South Sudan and others.

These are variable; from none, to mild, moderate and severe.

The classic symptoms of cholera include:

The symptoms may start from few hours to about five days after exposure to the vibrio cholerae.

Treatment of cholera is simple and effective if it is provided on time. Delay in treatment leads to severe consequences and in many cases death.

Treatment of cholera cases include the following:

The highest concern for cholera sufferers is the loss of fluids and salts from the body. For this reason, cholera patients are advised, in mild cases, to take plenty of fluids orally. The fluid may be as simple as mild sugar and salt water, or coconut water, or sugar cane juice. Pre-formulated commercial oral rehydration salts (ORS) are alternative sources of supplements to use in preparing clean water for drinking in mild cases of cholera.

Up to 80% of Cholera cases have been successfully treated with ORS in Africa.

Severely dehydrated patients may require intravenous fluids like 0.9% normal saline, lactated ringers, or 5% dextrose in water, etc., to restore hydration rapidly.

Antibiotics are not necessary for treatment of cholera but yes, it does help in moderate to severe cases to reduce the amount of both diarrhea and vomiting. With antibiotics both duration and intensity of the diseases can be reduced.

The World Health Organisation recommends a multifaceted approach to prevent and control cholera, and to reduce deaths.

The approach includes:

Top 10 vaccine preventable diseases in Africa (Slideshow)

Source:

World Health Organisation. Cholera – Overview, factsheet and more

Published: December 8, 2019

© 2019. Datelinehealth Africa Inc. All rights reserved.

DATELINEHEALTH AFRICA INC., is a digital publisher for informational and educational purposes and does not offer personal medical care and advice. If you have a medical problem needing routine or emergency attention, call your doctor or local emergency services immediately, or visit the nearest emergency room or the nearest hospital. You should consult your professional healthcare provider before starting any nutrition, diet, exercise, fitness, medical or wellness program mentioned or referenced in the DatelinehealthAfrica website. Click here for more disclaimer notice.