Cerebral Malaria Explained: Cause, Symptoms and Treatment

By Kelechi Nwaowu, BNSc., RN, RM. Freelance Health and Wellness Writer. Medically reviewed by Dr. A. Biakolo, MBBS.

An African child with malaria symptoms lying in bed with a caregiver checking her temperature with her hand. Image Credit| Leonardo AI

Malaria is a familiar disease in Africa. Most people have experienced the fever, chills, and body aches that come with malaria infection. However, there is a form of malaria that is far more dangerous than the usual type, it's called cerebral malaria. This condition affects the brain and can kill within hours if not treated immediately. Understanding cerebral malaria can help African families recognize danger signs early and seek lifesaving treatment.

Cerebral malaria is the most severe neurological complication of malaria caused by the Plasmodium falciparum parasite (1). It is a medical emergency that happens when the malaria parasite affects the brain, leading to unconsciousness, seizures, and potential death.

The World Health Organization defines cerebral malaria as a condition where a person with Plasmodium falciparum parasites in their blood falls into a coma that lasts at least one hour after a seizure ends or after low blood sugar is corrected, and no other cause can explain the coma (2). In everyday terms: If a person has a malaria fever and then becomes so sleepy they cannot wake up, or if they act very confused and 'lost' after a fit (seizure), you should treat it as cerebral malaria and get to a hospital immediately.

In 2024, malaria caused an estimated 610,000 deaths worldwide. Most of these losses, about 95% happened in Africa, and 76% were children under the age of 5 (3). Among the various forms of the disease, cerebral malaria is one of the most frequent causes of death in severe malaria cases (4).

Simple malaria, also called uncomplicated malaria, causes fever, chills, headache, body aches, and weakness. While these symptoms are uncomfortable, they respond well to treatment with antimalarial drugs, and people recover fully within days.

Cerebral malaria is completely different. In cerebral malaria, the infection affects the brain, causing serious neurological problems. The person may have seizures, become confused, lose consciousness, and slip into a coma. Without immediate hospital treatment, cerebral malaria kills quickly (4).

The key difference is brain involvement. In simple malaria, the parasites stay in the bloodstream and cause general symptoms. In cerebral malaria, infected red blood cells stick to the walls of blood vessels in the brain, blocking blood flow and damaging brain tissue (1).

|

Cerebral malaria is malaria that has reached the brain — and it is always a medical emergency. |

The malaria parasite does not actually enter the brain tissue itself. Instead, it causes damage while remaining inside blood vessels in the brain (1). Here is how and why the damage happens:

Infographics explaining why and how the brain swells in patients with cerebral malaria.AI generated from ChatGPT. Click on image to enlarge.

The mosquito transmits Plasmodium falciparum to infects red blood cells.

The Plasmodium falciparum changes the surface of the red blood cells as the parasites produce special proteins that make the infected red blood cells sticky.

These sticky cells then attach to the walls of tiny blood vessels throughout the body, especially in the brain (2).

The sticky red cells attaching to tiny blood vessels of the brain cause reduced blood flow to the brain and consequently reduced oxygen and nutrient supply.

Reduced oxygen and nutrient supply to the brain causes the brain to swell.

Step VI: Brain Inflammation Causes Leaky Fluid into Brain Tissue

As the body’s defense system (the immune system) tries to fight back the infection, it releases strong chemicals (cytokines) to kill the parasite. However, these chemicals can accidentally leak through the brain's protective shield, called the blood-brain barrier (2). Once this shield is damaged, harmful fluids leak into the brain tissue, causing even more swelling and damage.

Step VII: Brain Swelling and Leaky Fluid Causes Harmful Rise in Brain Pressure

Because the brain lies inside the hard bone of the skull, it has no room to expand following the swelling and fluid leak into the brain tissue. This creates dangerous pressure that may lead to seizures and coma.

Africa carries the heaviest burden of malaria in the world. In 2024, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 95% of all malaria cases and 96% of malaria deaths globally (3). This means that almost all malaria deaths happen in Africa.

Cerebral malaria primarily affects children under 3 and 5 years old in Sub-Saharan Africa (1). A study in Nigeria from 2019 to 2022 found that of 948 cases of severe malaria in children, 284 cases were cerebral malaria, representing 30% of severe malaria cases (5).

Related: Be Aware: Not Every Fever in African Adults Is Caused By Malaria.

Several factors make cerebral malaria especially common in Nigeria and other African countries:

Malaria transmission is very high in tropical Africa. People get bitten by infected mosquitoes frequently, leading to repeated infections throughout life. Nigeria alone reported an estimated 68 million malaria cases and 194,000 deaths in 2021, accounting for 27% of the global malaria burden (5). Nigeria, along with the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Niger, accounts for over half of all malaria deaths in Africa in 2024 (3).

This burden creates a constant strain on Nigeria’s hospitals and pediatric wards. During peak malaria seasons, healthcare facilities are often overwhelmed, with beds full and medical staff working around the clock to treat severe cases that could have been prevented with early care.

Many children in rural areas do not reach health facilities quickly enough when malaria symptoms start. A 2022 study in Malawi found that delayed presentation to hospital care is associated with long-term brain damage in children with cerebral malaria (6). Every hour counts when treating cerebral malaria.

Many African communities lack nearby hospitals with intensive care facilities needed to treat cerebral malaria properly. Even when families recognize the emergency, getting to a hospital can take many hours.

Unlike some countries where malaria is seasonal, many parts of Nigeria and West Africa have malaria transmission all year round, giving the parasite constant opportunities to infect people.

Cerebral malaria is triggered by one specific parasite that behaves differently from regular malaria, leading to life-threatening brain complications.

Plasmodium falciparum is the deadliest malaria parasite and is responsible for the most clinical cases and deaths (4). This parasite is particularly dangerous because of its ability to make infected red blood cells stick to blood vessel walls in vital organs like the brain, leading to severe complications.

The parasite spreads when an infected female Anopheles mosquito bites a person and injects the parasite into their bloodstream. The parasite then travels to the liver, multiplies, and returns to the bloodstream to invade red blood cells. Inside the red blood cells, the parasites multiply again, eventually bursting the cells and releasing more parasites to infect other red blood cells.

Children under 5 years old and pregnant women face the highest risk of developing cerebral malaria and require special protection. Image Credit: ChatGPT. Click on image to enalrge.

Cerebral malaria does not affect everyone equally. Certain groups face much higher risks:

This age group accounts for 75% of all malaria deaths (3). Young children have not developed immunity to malaria because they have not been exposed to the parasite enough times for their immune systems to learn how to fight it effectively. In sub-Saharan Africa, cerebral malaria mainly affects children under 5 years old (1).

A 2024 study in Uganda found that among children aged 6 to 59 months admitted with severe malaria, a significant proportion developed cerebral malaria (7). The study confirmed that children in this age group remain highly vulnerable to this deadly complication.

Pregnant women are more likely to develop severe malaria compared to non-pregnant women (3). During pregnancy, the immune system changes, making women more susceptible to malaria infection. When pregnant women get malaria, they risk developing cerebral malaria, severe anemia, and other life-threatening complications. Additionally, malaria during pregnancy can harm the unborn baby, leading to low birth weight, premature delivery, or stillbirth (3).

To stay safe, pregnant women should attend antenatal clinics as soon as they know they are pregnant. Starting these visits early allows healthcare workers to provide the necessary preventive medicine and mosquito nets to protect both the mother and the baby.

Adults who have grown up in malaria-endemic areas usually develop some immunity that protects them from severe malaria, though they can still get sick. However, adults who travel to malaria areas from non-endemic regions have no immunity and can develop cerebral malaria just like young children. A 2023 case report described a 61-year-old man who returned from the Democratic Republic of the Congo with fever, fatigue, and confusion, and was diagnosed with cerebral malaria (8).

HIV weakens the immune system, making it harder for the body to fight malaria. People with HIV have a higher risk of developing severe malaria, including cerebral malaria.

Early recognition of cerebral malaria symptoms can mean the difference between life and death. Parents, teachers, and caregivers must know what warning signs to watch for.

Cerebral malaria often starts with symptoms similar to simple malaria. However, these symptoms are usually more severe and worsen quickly:

These early symptoms can appear suddenly, within just a few days of being bitten by an infected mosquito. In young children, parents may notice that the child becomes irritable, cries more than usual, and does not want to play.

For more guidance on managing fever in children at home before reaching the hospital, read: Tips for African Parents on Caring for a Child with Fever at Home.

AI generated infographics on the early and emergency signs of Cerebral Malaria. Image Credit| Gemini AI. Click on image to enlarge.

If malaria progresses to cerebral malaria, emergency neurological symptoms appear. These symptoms require immediate medical attention:

|

Any seizure or loss of consciousness in someone with malaria symptoms is a hospital emergency. Do not wait for the person to wake up on their own. |

A 2025 study in The Gambia found that among adult patients with cerebral malaria, 52.6% of those who died did so within the first 24 hours of admission to hospital (9). This emphasizes the urgent nature of cerebral malaria and the need for immediate treatment.

African healthcare worker examining blood for malaria diagnosis with RDT kit on the table. Image Credit: Gemini AI. Click on image to enlarge.

Diagnosing cerebral malaria requires both clinical assessment and laboratory tests. When a patient arrives at the hospital with fever and altered consciousness, doctors follow specific steps:

1. Clinical Assessment: The doctor examines the patient's level of consciousness using a scoring system. They check if the patient can wake up, respond to questions, and obey commands. They also look for signs of brain involvement such as seizures, abnormal eye movements, or unusual body posturing.

2. Blood Tests for Malaria: The most important test is checking for malaria parasites in the blood. This is done in two ways:

3. Ruling Out Other Causes: The doctor must make sure that no other condition is causing the coma. They may need to test for conditions like meningitis (infection of the coverings of the brain), encephalitis (brain inflammation), poisoning, or metabolic problems. Sometimes a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) is performed to examine cerebrospinal fluid and rule out bacterial or viral brain infections.

4. Additional Tests: The doctor may order other tests to check how severely the disease has affected the body, including tests for blood sugar levels (malaria can cause dangerously low blood sugar), kidney function, liver function, and blood counts to check for anemia.

5. Retinal Examination: In some specialized centers, doctors examine the back of the eye (retina) with an ophthalmoscope. Specific changes in the retina are highly suggestive of cerebral malaria and help distinguish it from other causes of coma (2).

The challenge with diagnosing cerebral malaria is that the WHO clinical criteria can sometimes include patients who have coma from other causes that are not malaria related. If someone is in a coma for a different reason, a blood test might still find malaria parasites, even if they are not the cause of the coma. This is why additional tests like retinal examinations are valuable (2).

Cerebral malaria is a medical emergency that requires immediate hospital treatment. Delay in starting treatment significantly increases the risk of death or permanent brain damage. While this is a serious condition, it is treatable. Most patients who receive the correct hospital treatment early make a full recovery

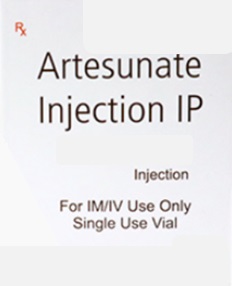

Intravenous artesunate is a first line medication used in treating cerebral malaria.

The gold standard treatment for cerebral malaria is intravenous artesunate, an artemisinin derivative (1). Artesunate is given through a vein (intravenously) because the patient is unconscious and cannot swallow tablets.

A large study in 11 African centers in 2010 showed that children with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria had lower mortality rates when treated with intravenous artesunate compared to intravenous quinine (10). Children treated with artesunate also had reduced incidence of coma, seizures, and post-treatment low blood sugar. Based on this evidence, the World Health Organization recommends intravenous artesunate as the preferred treatment for severe malaria, including cerebral malaria.

Artesunate is given at 0 hours, 12 hours, and 24 hours, then once daily until the patient can take oral medication.

Once the patient regains consciousness and can swallow, they complete the treatment with a full course of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) tablets for three days. The most common ACTs used in Africa are artemether-lumefantrine and artesunate-amodiaquine (11).

Using artemisinin (Artesunate) alone can lead to the parasite coming back after treatment. Combining artemisinin with another antimalarial drug ensures that all parasites are killed and prevents the development of drug resistance (11).

Artesunate is safe for pregnant women and children. For pregnant women in the first trimester where there is uncertainty about artemisinin safety, intravenous artesunate is still recommended because the benefits of treating severe malaria far outweigh any theoretical risks (11).

Treatment of cerebral malaria is not just about killing the parasite. Supportive care in the hospital is equally important to keep the patient alive while the antimalarial drugs work.

1. Managing Seizures: Seizures are common in cerebral malaria and can cause further brain damage. Doctors give anticonvulsant medications such as diazepam or phenobarbital to stop seizures. Repeated seizures may require continuous medication to prevent them from recurring.

2. Fluid Management: Maintaining the right fluid balance is critical. Too little fluid causes dehydration and low blood pressure, which reduces blood flow to the brain. Too much fluid can cause the brain to swell even more or lead to fluid in the lungs. Doctors carefully monitor fluid intake and output, giving intravenous fluids at the right rate.

3. Treating Low Blood Sugar: Malaria parasites consume glucose from the blood, and certain antimalarial drugs can also lower blood sugar. Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) can cause seizures and worsen coma. Doctors regularly check blood sugar levels and give glucose if needed.

4. Oxygen Therapy: If the patient has difficulty breathing or low oxygen levels, they receive oxygen through a mask or nasal tubes. In severe cases, the patient may need mechanical ventilation (a breathing machine).

5. Treating Anemia: Severe malaria often causes anemia because the parasite destroys red blood cells. If anemia is severe, the patient may need a blood transfusion to replace lost red blood cells.

6. Monitoring and Intensive Care: Patients with cerebral malaria need close monitoring in a hospital intensive care unit or high-dependency unit. Medical staff regularly checks vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, breathing rate and temperature), level of consciousness, and look for complications.

7. Treating Complications: Cerebral malaria can affect multiple organs. Doctors must watch for and treat kidney failure, liver problems, lung complications, and bleeding disorders.

Even with medical care, cerebral malaria remains dangerous.

About 20% of children and 30% of adults with the condition do not survive.

Among survivors, about 15% to 20% may have long-term issues like seizures or learning difficulties (1). However, these risks are much lower when treatment starts early. Fast action at the first sign of danger is the best way to improve the chance of a full recovery.

Preventing malaria is far better than treating it. Because Plasmodium falciparum causes cerebral malaria, preventing malaria infection prevents cerebral malaria.

|

How families can reduce risk of cerebral malaria:

|

AI generated infographics showing multiple malaria prevention strategies including nets, spraying, medication and vaccines. Image Credit| Gemini AI Cick on image to enlarge.

Insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), particularly long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs), are one of the most effective tools for preventing malaria. These nets are treated with insecticides that kill mosquitoes that come into contact with them.

African woman sleeping under insecticide-treated mosquito net for malaria prevention. Image Credit| World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa Click on image to enlarge.

Malaria-carrying Anopheles mosquitoes bite mainly between dusk and dawn, when people are sleeping. Sleeping under an insecticide-treated net creates a protective barrier. Even if mosquitoes enter the sleeping area, they are killed or repelled by the insecticide on the net before they can bite.

Since 2004, almost 2.5 billion ITNs have been distributed globally, with 2.2 billion (87 per cent) distributed in sub-Saharan Africa (12). In 2021, 66% of households in sub-Saharan Africa owned at least one ITN, compared to just 5% in 2000 (12). This massive scale-up of ITN distribution has contributed significantly to reducing malaria cases and deaths.

For maximum protection, everyone in the household, especially young children and pregnant women, should sleep under an ITN every night. The net should be tucked in carefully around the sleeping mat or bed so mosquitoes cannot enter from below. Nets should be checked regularly for holes and repaired or replaced when damaged.

Applying insect repellent lotions or sprays to exposed skin can provide additional protection against mosquito bites. Repellents containing DEET, Icaridin, or IR3535 are most effective (3). They should be applied to all exposed skin before going outdoors in the evening or early morning when mosquitoes are most active.

This involves spraying the inside walls and ceilings of houses with long-lasting insecticides. Mosquitoes that rest on these surfaces after feeding are killed. Indoor residual spraying provides protection for several months. IRS, combined with ITNs, represents the two core interventions for malaria vector control (3).

Reducing mosquito breeding sites around homes helps lower malaria transmission. This includes:

III. Preventing Malaria in Children: Intermittent Preventive Treatment

Intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) is a strategy where antimalarial drugs are given to high-risk groups at specific times, regardless of whether they have malaria. This helps prevent malaria before it causes harm.

Related: Antenatal care is crucial for preventing malaria in pregnancy. Learn more about Services You Should Expect During Antenatal Care.

In October 2021, the World Health Organization recommended the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine for children in areas with moderate to high malaria transmission. In October 2023, WHO also recommended the R21/Matrix-M vaccine (3). These vaccines provide partial protection against malaria and are used alongside other prevention measures. The vaccines do not provide complete protection, so children must still use bed nets and receive prompt treatment if they get sick.

|

Vaccines add protection — they do not replace bed nets. |

For more on Africa's progress in malaria control, see: WHO Certifies Egypt Malaria-Free.

Cerebral malaria is a medical emergency that kills quickly without immediate treatment. The disease occurs when Plasmodium falciparum parasites cause infected red blood cells to block blood vessels in the brain, leading to brain swelling, seizures, coma, and death. Children under 5 and pregnant women face the highest risk.

Africa, particularly Nigeria and other West African countries, bears the heaviest burden of cerebral malaria. Early recognition of warning signs like high fever, severe headache, vomiting, and especially altered consciousness or seizures is critical. If you suspect cerebral malaria, rush the person to the nearest hospital immediately. Every minute counts.

Treatment with intravenous artesunate is highly effective when started early, but delays increase the risk of death or permanent brain damage. Prevention through sleeping under insecticide-treated bed nets, using indoor spraying, giving children intermittent preventive treatment, and ensuring pregnant women receive preventive drugs can dramatically reduce the risk of cerebral malaria.

Cerebral malaria is a deadly disease, but it is preventable and treatable. Communities that recognize symptoms early and support quick hospital visits save lives. By working together to use treated mosquito nets and seek early care, we can protect our children and reduce the burden of this disease in Nigeria and across Africa.

1. Song X, Wei W, Cheng W, Zhu H, Wang W, Dong H, Li J. Cerebral malaria induced by plasmodium falciparum: clinical features, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2022 Jul 25;12:939532. Available from here.

2. Muppidi P, Wright E, Wassmer SC, Gupta H. Diagnosis of cerebral malaria: Tools to reduce Plasmodium falciparum associated mortality. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2023 Feb 9;13:1090013. Available from here.

3. World Health Organization. Malaria [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 Dec 4 [Cited 2026 Jan 30]. Available from here.

4. Akide Ndunge OB, Kilian N, Salman MM. Cerebral malaria and neuronal implications of plasmodium falciparum infection: From mechanisms to advanced models. Advanced Science. 2022 Dec;9(36):2202944. Available from here.

5. Ibrahim OR, Issa A, Babatunde RT, Alao MA. Clinical and laboratory predictors of poor outcomes in pediatric cerebral malaria in Nigeria. Oman Medical Journal. 2024 Nov 30;39(6):e692. Available from here.

6. Borgstein A, Zhang B, Lam C, Gushu MB, Liomba AW, Malenga A, Pensulo P, Tebulo A, Small DS, Taylor T, Seydel K. Delayed presentation to hospital care is associated with sequelae but not mortality in children with cerebral malaria in Malawi. Malaria Journal. 2022 Feb 22;21(1):60. Available from here.

7. Mseza B, Kumbowi PK, Nduwimana M, Banga D, Busha ET, Egesa WI, Odong RJ, Ndeezi G. Prevalence and factors associated with cerebral malaria among children aged 6 to 59 months with severe malaria in Western Uganda: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. BMC pediatrics. 2024 Nov 6;24(1):704. Available from here.

8. Roberson MT, Smith AT. Cerebral malaria in a patient with recent travel to the Congo presenting with delirium: a case report. Clinical Practice and Cases in Emergency Medicine. 2020 Oct 19;4(4):533. Available from here.

9. Bittaye SO, Jagne A, Jaiteh LE, Amambua?Ngwa A, Sesay AK, Ramirez WE, Ramos A, Effa E, Nyan O, Njie R. Cerebral Malaria in Adults: A Retrospective Descriptive Analysis of 80 Cases in a Tertiary Hospital in The Gambia, 2020–2023. Health science reports. 2025 Jan;8(1):e70401. Available from here.

10. Dondorp AM, Fanello CI, Hendriksen IC, Gomes E, Seni A, Chhaganlal KD, Bojang K, Olaosebikan R, Anunobi N, Maitland K, Kivaya E. Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): an open-label, randomised trial. The Lancet. 2010 Nov 13;376(9753):1647-57. Available from here.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment of severe malaria [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; 2024 Mar 27 [Cited 2026 Jan 30]. Available from here.

12. Chanda E. Malaria and vector control situation with focus on ITNs [Internet]. Alliance for Malaria Prevention; 2023 May [Cited 2026 Jan 30]. Available from here.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Malaria drug strategies [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2024 Sep 23 [Cited 2026 Jan 30]. Available from here.

Published: February 17, 2026

© 2026. Datelinehealth Africa Inc. All rights reserved.

Permission is given to copy, use, and share content freely for non-commercial purposes without alteration or modification and subject to source attribution.

DATELINEHEALTH AFRICA INC., is a digital publisher for informational and educational purposes and does not offer personal medical care and advice. If you have a medical problem needing routine or emergency attention, call your doctor or local emergency services immediately, or visit the nearest emergency room or the nearest hospital. You should consult your professional healthcare provider before starting any nutrition, diet, exercise, fitness, medical or wellness program mentioned or referenced in the DatelinehealthAfrica website. Click here for more disclaimer notice.